Life That We Love

Life That We LoveIn response to the lavish outpouring of life, yet mindful of the human potential to waste and spoil and upset nature’s balance, F W Boreham, in many editorials, highlighted the social responsibilities of protecting and preserving nature. [1] Working from the premise that “it is life that we love ... therefore we should not kill animals”,[2] Boreham wrote editorials calling for the prevention of cruelty to animals[3] and he attacked the “blood lust of the British” and “the vogue of the big game hunter” that resulted in certain animal species being in danger of extinction.[4]

Preserve the Birds

Boreham’s concern for birds led to his plea for the saving of hedges[5] and, writing from Tasmania, the most wooded state of the country, he sounded the urgency of preserving the habitats of birds that were in peril of extinction.[6] He lambasted the installation of air beacons around the world that “have wrought havoc among the vast flights of migratory birds”,[7] he claimed that “the rapid increase of population [in some countries] is threatening the extermination of the loveliest and most valuable of the feathered species” and he denounced “the havoc wrought by the insatiable demands of the milliner”.[8]

Save the Forests

Calling the forest “man’s oldest and most faithful friend, and one towards whom he is inclined to turn with increasing reverence and affection as the ages go by”,[9] in 1920 Boreham joined a growing number of people[10] in castigating those who carelessly cleared the forests and bush, saying, “Australia cannot afford to part with its trees”.[11] While mindful of the instinct for chopping to which Boreham’s heroes, W E Gladstone and Richard Jeffries, succumbed, he expressed in 1928 his pleasure at “the popularisation of Arbor Day” and other government initiatives, saying to his readers that “we should all of us apply ourselves to a wholesale orgy of tree-planting”.[12]

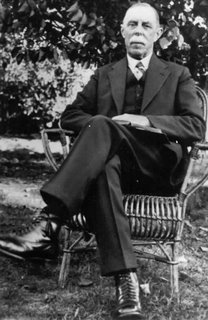

Geoff Pound

Image: “a wholesale orgy of tree-planting.”

[1] Boreham, Mercury, 25 September 1917.

[2] Boreham, Mercury, 9 June 1917; F W Boreham, The home of the echoes (London: The Epworth Press, 1921), 82.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 26 June 1915.

[4] Boreham, Mercury, 21 March 1914.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 5 July 1930.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 13 September 1913; 26 October 1940.

[7] Boreham, Mercury, 20 April 1929.

[8] Boreham, Mercury, 26 October 1940.

[9] Boreham, Mercury, 28 June 1924.

[10] Ann R M Young, Environmental change in Australia since 1788 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1996), 74-75.

[11] Boreham, Mercury, 10 July 1920.

[12] Boreham, Mercury, 9 June 1928.

Packet of Surprises

Packet of Surprises