Inherent in Boreham’s theme of “making the best of ourselves” was the recognition that each person has a different ability so that each must “bring to perfection the best of which he or she is capable”.[1]

Inherent in Boreham’s theme of “making the best of ourselves” was the recognition that each person has a different ability so that each must “bring to perfection the best of which he or she is capable”.[1]In one of many editorials that valued the individual, Boreham said, “The thing that makes humanity so perennially fascinating is its infinite capacity for exceptions.”[2] While not clarifying what type of exceptions he had in mind, he wrote elsewhere of “the value of the freak” and “the black sheep”, the need to study and treasure people who are exceptions and the conviction that “different children need to be cherished”.

In an article about the life of Beethoven, Boreham said, “The glory of Beethoven was that he was essentially a rebel [and] ... to such rebels ... the world owes a debt it will never be able to compute”.[3]

Most certainly Boreham’s experience of having a physically and mentally disabled child named Stella, “the only fragile flower in our garden”,[4] gave to his writing a deep appreciation of the value that such individuals bring to the world. Writing about, ‘The care of the feeble-minded’,[5] when Stella was seven, Boreham emphasized the “long series of gradations of mental deficiency” (as distinct from being either ‘sane or insane’).

In this important statement in 1914, a few years after the Australian government had introduced the Old Age Pension (1909) and the Invalid Pension (1910), Boreham encouraged society to implement preventative and remedial measures for the disabled. He applauded the rise of specially qualified teachers and supported the move for all large centres to have Day Schools as well as Residential Schools.

Rather than keeping the disabled remote from society, Boreham hoped that they would be “saved to the community” and that “by a little sympathetic treatment [they] might be made into useful and intelligent citizens.”

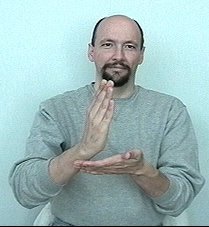

In 1924 Boreham wrote about the deaf and dumb and their experience of “the paralysis of silence”. Identifying the additional pain of public prejudice, Boreham claimed, “No country has done more to abolish it than has Australia.”[6]

Geoff Pound

Image: Experiencing “the paralysis of silence.”

[1] Boreham, Mercury, 10 September 1955.

[2] Boreham, Mercury, 20 January 1934.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 6 March 1943.

[4] Boreham, My pilgrimage, 190-191.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 27 February 1914.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 19 February 1924.

One of the reasons why Boreham grew silent on war issues and loud on biographical sermons and editorials was, according to T Howard Crago, his biographer, because his reading of Gibbon’s Decline and fall had given him the insight:

One of the reasons why Boreham grew silent on war issues and loud on biographical sermons and editorials was, according to T Howard Crago, his biographer, because his reading of Gibbon’s Decline and fall had given him the insight: Dr F W Boreham identified growth in inclusivity as a sign of a person realizing their full potential and he made his point through the use of colourful Australian imagery:

Dr F W Boreham identified growth in inclusivity as a sign of a person realizing their full potential and he made his point through the use of colourful Australian imagery:

Everlasting Explorers

Everlasting Explorers