This posting is part of a series on F W Boreham and the authors who influenced his literary style. This article is the first of two instalments on the historian, Thomas Macaulay (1800-1859)[1]

This posting is part of a series on F W Boreham and the authors who influenced his literary style. This article is the first of two instalments on the historian, Thomas Macaulay (1800-1859)[1]:

Strength of OpinionsIn an essay entitled, ‘The influence of Macaulay’, Boreham affirmed that Thomas Babbington Macaulay, the English journalist turned historian, essayist and politician “has more than any other man influenced the writing of the English tongue”.

[2] Boreham himself was profoundly influenced by Lord Macaulay and, after reading and marking carefully

The history of England and

The life and letters of Lord Macaulay in March and April 1902, he wrote on the last page of his copy, “Read with immense profit, Apl 1902”.

[3]Boreham recognised Macaulay’s works as “a manual for the uneducated”

[4] and people like him who had commenced a discipline of self-education.

[5] While Boreham affirmed Macaulay for advocating “the importance of forming one’s own opinions and not seeing through the eyes of others”,

[6] Macaulay’s strength of convictions appeared to have shaped Boreham’s views enormously, especially concerning the importance of a nation taking pride in its achievements,

[7] the virtue of patriotism,

[8] the value of history,

[9] the progress of society

[10] and the things that make for citizenship.

[11]How History Should Be WrittenMacaulay’s

History extended Boreham’s knowledge of his homeland (albeit from a conservative, old-fashioned perspective) and confirmed his convictions about how history should be written.

[12] Boreham’s underlining of a reference to a compliment paid to Macaulay (which he ‘really prized’) for “having written a history which working men can understand”

[13] suggests a stimulus for Boreham in adopting Macaulay’s patient practice of reworking and polishing to produce a clear, simple writing style.

[14] While it has been noted that Boreham admired Gibbon and Rutherford for the clarity of their expression, Thomas Macaulay, who also valued this quality, lamented that so few shared this conviction: “How little the all important art of ‘making meaning pellucid’ is studied now! Hardly any popular writer except myself thinks so.”

[15]Imaginative History

Macaulay’s aim to write a history that was instructive, entertaining and universally intelligible led him to “get as fast as he could over what was dull, and to dwell as long as he could on what could be made picturesque and dramatic”.

[16] While these traits were admirable, the historian John Clive said they “may also have acted as impediments to the genuine historical imagination which is more concerned with the unvarnished truth than with enlivening it”.

[17]First Hand ObservationBoreham was impressed by William Thackeray’s tribute that Macaulay “reads twenty books to write a sentence; he travels a hundred miles to make a line of description”.

[18] The aspiring author was also inspired by Macaulay to take scrupulous care in checking out references

[19] and visiting whenever possible the historical sites that related to his subjects.

[20] Macaulay’s habit of travelling to the scene of his subject developed his eye for detail and involved collecting a large store of images—“images which his photographic memory retained, so to speak, as negative film to be developed into positives when he came to write”.

[21]Geoff Pound

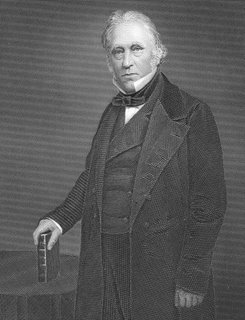

Image: Thomas Macaulay

[1] Thomas Macaulay was an English historian, essayist, politician and poet. He contributed to the

Edinburgh Review and wrote biographical essays on John Bunyan and the history of England. More information on Lord Macaulay can be found in the

Bloomsbury guide to English literature, 689.

[2] Boreham,

Mercury, 25 September 1920.

[3] Inscribed by Boreham in G O Trevelyan,

The life and letters of Lord Macaulay, pop. ed. (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1899), 688. This book is in F W Boreham Collection, Whitley College.

[4] Boreham,

Mercury, 25 September 1920.

[5] Boreham,

Mercury, 25 September 1920.

[6] Boreham,

Mercury, 11 January 1930.

[7] Boreham,

Mercury, 26 October 1918.

[8] Boreham,

Mercury, 3 November 1934.

[9] Boreham,

Mercury, 19 August 1933.

[10] Boreham,

Mercury, 9 March 1935.

[11] Boreham,

Mercury, 4 November 1944.

[12] G S Fraser, ‘Macaulay’s style as an essayist’,

Review of English literature 1 (4 October 1960): 9.

[13] Trevelyan,

The life and letters of Lord Macaulay, 509.

[14] Trevelyan,

The life and letters of Lord Macaulay, 502.

[15] Trevelyan,

The life and letters of Lord Macaulay, 502.

[16] Macaulay’s journal entry on 3 March 1853 is cited in John Clive, ‘Macaulay’s historical imagination’,

Review of English literature 1 (October 1960): 22.

[17] Clive, ‘Macaulay’s historical imagination’, 27.

[18] See Boreham’s underlining in his copy of Trevelyan,

The life and letters of Lord Macaulay, 495. Also Boreham’s further reference to this quote in his copy of T B Macaulay,

History of England, vol. 1. (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1899), title page, in F W Boreham Collection, Whitley College.

[19] Boreham wrote of the rich research facilities of the Melbourne Public Library [now the State Library of Victoria] which assisted his scholarship, in Boreham,

My pilgrimage, 197.

[20] Boreham wrote extensively about visiting sacred sites and the way it forged a link with the personality who had died, in Boreham,

When the swans fly high, 157.

[21] Clive, ‘Macaulay’s historical imagination’, 22.

This is another article on the writers that shaped the literary style of F W Boreham. This posting looks at Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881)[1]:

This is another article on the writers that shaped the literary style of F W Boreham. This posting looks at Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881)[1]:

This posting is part of a series on F W Boreham and the authors who influenced his literary style. This article is about the influence of the author, John Bunyan (1628-1688)

This posting is part of a series on F W Boreham and the authors who influenced his literary style. This article is about the influence of the author, John Bunyan (1628-1688) This posting is part of a series on F W Boreham and the authors who influenced his literary style. This article is the second of two instalments on the historian, Thomas Macaulay (1800-1859):

This posting is part of a series on F W Boreham and the authors who influenced his literary style. This article is the second of two instalments on the historian, Thomas Macaulay (1800-1859):