The Rev David Enticott is a pastor and staff member of Whitley College in Melbourne. He is writing a thesis on the preaching of F W Boreham, having already written a long essay on the influences which shaped Boreham's preaching from 1891-1894 (the English period). David recently gave a lecture on F W Boreham in a lecture series at Whitley College entitled, Faith in the Public Sphere. Here is an excerpt from his lecture in which David focuses on Boreham's preaching and writing from Hobart during the First World War:

The Rev David Enticott is a pastor and staff member of Whitley College in Melbourne. He is writing a thesis on the preaching of F W Boreham, having already written a long essay on the influences which shaped Boreham's preaching from 1891-1894 (the English period). David recently gave a lecture on F W Boreham in a lecture series at Whitley College entitled, Faith in the Public Sphere. Here is an excerpt from his lecture in which David focuses on Boreham's preaching and writing from Hobart during the First World War:At the start of 1914 Boreham’s sermons were predominantly about timeless values. They were optimistic and filled with notes of “attractiveness, expectancy and triumph.” He preached one in January 1914 called; The Deep and the Shallows that was then turned into an article for the Australian Baptist.

In this sermon manuscript he drew from his love of nature and spoke of the rapture of the sea-side. He painted a picture for his listeners of picnickers by the sea and said that they were “ENTIRELY DETACHED FROM THE ACCIDENTS OF ANY PARTICULAR AGE. THE WORLD COULD CHANGE AS IT WILL AND THEY WOULD NOT KNOW IT.”[1]

In August 1914 the world did change. The seas of conflict swept the globe. And just as he did in his newspaper editorials for the Hobart Mercury, Boreham sought to ask the question of: where is God in the midst of war?

He engaged in deep theological reflection. On the 2nd of August 1914 he preached on the topic of the Comforter Divine. On the back of his sermon manuscript was the note: “preached on occasion of great crisis. Germany declared war on Russia.” He spoke to this uncertainty and offered a vision of a God of hope, strength and love.

For the remainder of 1914, his sermons took on more of a focus around the themes of: duty and obligation. While Howard Crago might have commented that Boreham’s sermons “were not flamboyant or jingoistic” the evidence suggests otherwise. Instead they were filled with fervour for the battle ahead.

A message preached on the 13th of September was something of a call to arms, that was given the title: The Second Mile. He used the example of Christ to show that Jesus not only fulfilled his duties by going the first mile, but he went on doing good by going the second.

One sermon took up President Woodrow Wilson’s favourite text and another spoke of the King’s faith. The latter spoke of: the importance of enlisting, wearing the uniform and then adorning the uniform with medals and meritorious service. Howard Crago writes that during this time “recruiting was in full swing and some of the Tabernacle’s best young men were appearing in khaki.”

While we may not share his conclusions, these messages were: up to date, engaging, fresh, relevant and sharp. They were a mixture of the newspaper and the Bible. They were sharp, just like his editorials at the time. Then in 1915 the flavour of his sermons started to shift.

As families felt the full toll and cost of the war, he uttered words of comfort and consolation. Two months prior to the Gallipoli landing he brought a reflection upon Micah 7:8 that says: “When I sit in darkness, the Lord shall be a light unto me.”

He spoke of the problem of pain and started with an evocative story from the front line. It was told by Canon D.J.Stather-Hunt who was the Vicar of the Holy Trinity Church in Boreham’s birth-place- Tunbridge Wells. The story was of a soldier who had been shot across the eyes, with sight then being lost permanently in one eye.

The Chaplain upon seeing the soldier was moved with compassion, delved into his satchel and drew something from it. The contents were a small bag of lavender with a note that Stather Hunt read to the wounded soldier: It was Micah’s passage- when I sit in darkness, the Lord shall be a light unto me. The chaplain said to the soldier: “that sweet smell will remind you of home.”[2]

Boreham was unsure about whether to include this narrative and even added a question within his manuscript asking: “Is it morbid?” He believed though that it was evidence of an incarnational God able to turn terror to triumph. People needed such stories of comfort from the front-lines of battle.

But then as the war progressed Boreham became increasingly silent, just as he did in his editorials. Perhaps war fatigue had set in both for him and for his congregation. His sermons lost their spark, their sense of vital engagement.

As he looked out on regiments marching through the streets, broke bad news to families and comforted the bereaved, Boreham’s enthusiasm for the war and for engaging with the issues of his time, died down.

In Winter 1915, he preached a series called: The Happy Warrior- His Struggles, Reverses and Triumphs. The series ran from April to September and considered themes such as: “The Enemy- seen through the eyes of a savage”, “Buckling on the Sword”, “Decoy and Ambush” and the “Fight of the Foe.” However, this war was spiritual not physical. It took place upon an eternal battlefield rather than those in France and Africa.

By the end of the year Boreham’s messages returned to the timeless themes of spiritual satisfaction and stories from Samuel Wesley, Livingstone, C.H.Spurgeon and Dickens. He had moved from the public sphere to the eternal.

Something had been lost. In his autobiography he looked back on the First World War (ironically in 1941) and commented:

“My health was going from bad to worse. The trouble began with the outbreak of war. People said that I took things too seriously….I formed the conviction that at such a time a minister should remain among his own people…When hearts were breaking, and the comfort of the gospel was most sorely needed, I felt it my duty to be on the spot…such concentration..wore me down.”(My Pilgrimage, p.201)

Boreham’s story is a reminder that to engage in public issues theologically is to bear a certain cost. Boreham, early in the war, said in one of his sermons: “we must go so far, whether we will or no. You can never say, ‘thus far and no further.”[3]

Sadly Boreham himself found the cost of the war and of visiting families with the horrific news that their sons had just died on a foreign battlefield, too great.

His public theology could go so far and no further. It struggled under the weight of the war. A recent example of a similar cost is presented by the Melbourne Age cartoonist Michael Leunig, who in the midst of drawing many images against the Iraq War, found himself entered (against his wishes) in an Anti-Semitic Cartoon Competition. In the days following the furore Leunig found his peaceful farm invaded by television helicopters and crews.

In a sense he took up his cross, for daring to speak out against government policies. Yet he has continued to draw bravely and courageously! He has counted the cost, and kept going. This is not always easy, but it is an essential ingredient for a public theologian to have a thick skin!!!

[1] F.W.Boreham. 1914. “The Deep and the Shallows,” Sermon Manuscript, 11th of January, Hobart Tabernacle.

[2] F.W.Boreham. 1915. “The Luminous Dark”, Sermon Manuscript, 28th of Februuary, Hobart Tabernacle.

[3] F.W.Boreham. 1914. “The Second Mile”, Sermon Manuscript, 13th of September, Hobart Tabernacle.

Source: David Enticott. Many thanks David for allowing us to publish this part of your lecture on the Boreham Blog.

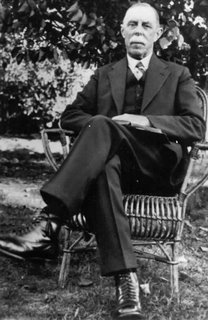

Image: David Enticott

Ideas?

Ideas? What Would You Say?

What Would You Say? Crucial Platform

Crucial Platform