This is a further article in a series that examines F W Boreham’s literary style that is most apparent in his newspaper editorials.

This is a further article in a series that examines F W Boreham’s literary style that is most apparent in his newspaper editorials.F W Boreham pitched his editorials at the emotional level of his readers. He highlighted the emotional transformation of his subjects that prompted a significant career, as when John Richard Green’s discovery of Edward Gibbon evoked “transports of excitement” and led him into a writing vocation.[1]

Boreham also described the impact of his subjects on the people of their time and context, as when he pictured the entry of the British politician William Cobbett into public life, by saying, “He plunged into the placidities of English life like a bull charging into a china shop.”[2] The quality of a character was often determined by the strength of the connection they forged with their contemporaries, as when the author Oliver Wendell Holmes “contrives to bind his reader to himself with hoops of steel”[3] or the philosopher Goethe was “destined to enchain half of Europe.”[4]

Frank Boreham wrote about the emotional effect in the original context, in the hope that his editorial might elicit a similar response within his own readers. The “magnetic”[5] or “electric”[6] personality of his subject and their ability to “wield magic,”[7] “mesmerise”[8] or “bewitch,”[9] are examples of the high-voltage vocabulary with which Boreham charged his editorials. He was also not averse to disclosing the impact of a subject on himself, as when he admitted, “Our nerves tingle in response to [Easter’s] stirring message.”[10]

Geoff Pound

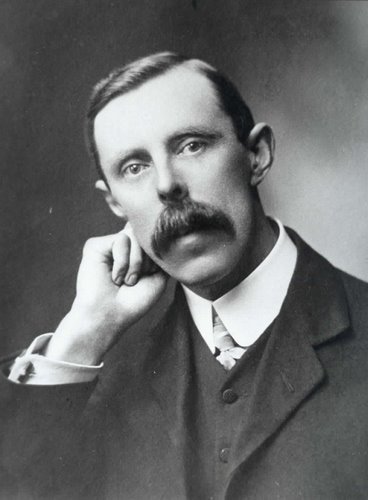

Image: “He plunged into the placidities of English life like a bull charging into a china shop.”

[1] F W Boreham, Mercury, 6 March 1948.

[2] Boreham, Mercury, 17 June 1950.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 29 August 1953.

[4] Boreham, Mercury, 27 August 1949.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 7 July 1934.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 17 June 1950.

[7] Boreham, Mercury, 21 May 1932.

[8] Boreham, Mercury, 30 April 1949.

[9] Boreham, Mercury, 6 March 1948.

[10] Boreham, Mercury, 5 April 1947.

Frank Boreham wrote about the emotional effect in the original context, in the hope that his editorial might elicit a similar response within his own readers. The “magnetic”[5] or “electric”[6] personality of his subject and their ability to “wield magic,”[7] “mesmerise”[8] or “bewitch,”[9] are examples of the high-voltage vocabulary with which Boreham charged his editorials. He was also not averse to disclosing the impact of a subject on himself, as when he admitted, “Our nerves tingle in response to [Easter’s] stirring message.”[10]

Geoff Pound

Image: “He plunged into the placidities of English life like a bull charging into a china shop.”

[1] F W Boreham, Mercury, 6 March 1948.

[2] Boreham, Mercury, 17 June 1950.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 29 August 1953.

[4] Boreham, Mercury, 27 August 1949.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 7 July 1934.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 17 June 1950.

[7] Boreham, Mercury, 21 May 1932.

[8] Boreham, Mercury, 30 April 1949.

[9] Boreham, Mercury, 6 March 1948.

[10] Boreham, Mercury, 5 April 1947.

What would you say were the hallmarks of F W Boreham’s writing? How would you describe his signature style?

What would you say were the hallmarks of F W Boreham’s writing? How would you describe his signature style?

“Years ago,” a friend told me once, “I used to take all my troubles to bed with me. I would lie there in the darkness with closed eyes, fretting and worrying all the time. I tossed and turned from one side of the bed to the other, as wide awake as at broad noon. As life went on, the habit grew upon me until it threatened to undermine my health. Then, one night, things reached a crisis. I could not sleep, so I rose from my bed and sat at the open window. The garden below and the fields were flooded in silvery moonlight. Not a breath of wind was stirring; the intense stillness was positively uncanny. The perfect tranquility mocked the surging tumult of my brain. How quiet the room seemed! And I had entered it—for what? My behavior seemed absurd in the extreme. Nature had wrapped around me her infinite calm; and here I was allowing all the worries of the world to fever my brain and break upon my rest! Why had I locked the office door so carefully if I wished all the ledgers and day books and order-forms to follow me home? Why had I closed the bedroom door so carefully if I wished all the cares of life to follow me in? I knelt down there at the window sill, with the delicious air of the still night caressing my face, and I then and there asked God to forgive me. And since then, when I've shut a door, I've shut a door!'

“Years ago,” a friend told me once, “I used to take all my troubles to bed with me. I would lie there in the darkness with closed eyes, fretting and worrying all the time. I tossed and turned from one side of the bed to the other, as wide awake as at broad noon. As life went on, the habit grew upon me until it threatened to undermine my health. Then, one night, things reached a crisis. I could not sleep, so I rose from my bed and sat at the open window. The garden below and the fields were flooded in silvery moonlight. Not a breath of wind was stirring; the intense stillness was positively uncanny. The perfect tranquility mocked the surging tumult of my brain. How quiet the room seemed! And I had entered it—for what? My behavior seemed absurd in the extreme. Nature had wrapped around me her infinite calm; and here I was allowing all the worries of the world to fever my brain and break upon my rest! Why had I locked the office door so carefully if I wished all the ledgers and day books and order-forms to follow me home? Why had I closed the bedroom door so carefully if I wished all the cares of life to follow me in? I knelt down there at the window sill, with the delicious air of the still night caressing my face, and I then and there asked God to forgive me. And since then, when I've shut a door, I've shut a door!'

F W Boreham writes about his first attempts to memorise some lines from Shakespeare and the way the speech stayed with him:

F W Boreham writes about his first attempts to memorise some lines from Shakespeare and the way the speech stayed with him: