Romance of Monotony

Romance of MonotonyIn the tradition of Joseph Turner and William Blake, F W Boreham wrote many editorials on the ordinary experience of discovering beauty and truth in the unexpected. As Turner in his painting ‘Rain, steam and speed’ portrayed beauty in a train rushing through rain, Boreham perceived fascination in prosaic sources, which included “the romance of monotony”,[1] “the romance of the bank”[2] and “the evolution of pockets”.[3] Such themes were mined for truth but the unexpected and unlikely topics were also designed to arrest attention and add to Boreham’s ‘surprise power’. Other titles which caught the interest of readers and reviewers included the editorials ‘Wet paint’,[4] ‘Second wind’,[5] ‘The fly in the ointment’,[6] ‘If’,[7] ‘Black sheep’[8] and ‘Keep off the grass’.[9] Additional stylistic devices included the use of graphic statements as in his definition of tea as “liquid prophecy”[10] or his description of an acorn as “a pocket edition of a forest”.[11]

Appreciator of Small Things

At times, Dr. Boreham’s treatment of ordinary things seemed unexpected because the subjects were quaint or even trivial. In the tradition of the early French essayist Michel de Montaigne,[12] who wrote about ‘Sleeping’, ‘Thumbs’ and ‘Smells and Odours’, Boreham addressed seemingly unimportant subjects such as ‘Left-handedness’,[13] ‘Hats’,[14] ‘The man in the moon’,[15] ‘Smoke’,[16] ‘Scarecrows’,[17] ‘Babies’,[18] ‘Boots and shoes’[19] and ‘Sugar and spice’.[20] This feature of Boreham’s editorial writing saturated his life and wider work. His contemporary, J J North, identified this characteristic when describing Boreham: “From the beginning of his career he has been a tremendous appreciator of small things. He was never guilty of despising them. He came from London to Mosgiel. Mosgiel was, if we may be forgiven the pun, saved from the moss by a solitary woollen mill. Otherwise it belonged to the cow and the plough and to the pleasant murmur of the bees”.[21]

In an assessment of the early part of his career, North described the Boreham trademark of presenting surprising and peculiar topics: “It was something to hear a man fresh from London town who would preach on the inner meaning of test matches and hitting your middle wicket, who, as the Boer war came on, could give a series on David’s valiant men who slew bears in pits on snowy days”.[22]

Trivial but Treasures

Frank Boreham was aware that others sometimes found his subjects preposterous yet upon reviewing his life he found justification for his style when declaring: “The things that most readily rush to mind are things that, at first blush, seem ridiculously trivial ... and yet the fact that the mind insists on treasuring such trifles, letting slip many incidents of greater apparent importance, may indicate that memory has a more just standard of values than we sometimes fancy”.[23]

Geoff Pound

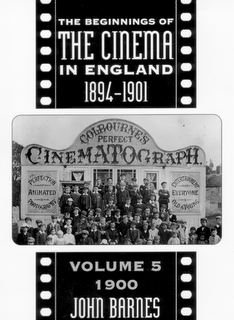

Image: Hitting your middle wicket.

[1] F W Boreham, Mercury, 24 November 1917.

[2] Boreham, Mercury, 30 September 1922.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 20 August 1921.

[4] Boreham, Mercury, 2 April 1938.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 31 May 1936.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 5 December 1931.

[7] Boreham, Mercury, 2 June 1923.

[8] Boreham, Mercury, 2 August 1924.

[9] Boreham, Mercury, 28 April 1945.

[10] Boreham, Mercury, 31 October 1936.

[11] F W Boreham, The crystal pointers (London: The Epworth Press, 1925), 217.

[12] Michel de Montaigne, The essayes of Michael Lord of Montaigne, trans. John Florio (London: George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., 1891), 134-135, 352, 156-157.

[13] F W Boreham, The silver shadow (London: The Epworth Press, 1919), 255.

[14] Boreham, Mercury, 31 October 1931.

[15] Boreham, Mercury, 31 July 1954.

[16] Boreham, Mercury, 4 November 1939.

[17] Boreham, Mercury, 29 May 1920.

[18] Boreham, Mercury, 30 April 1955.

[19] Boreham, Mercury, 10 July 1954.

[20] Boreham, Mercury, 13 March 1954.

[21] J J North, Australian Baptist, 16 February 1926.

[22] J J North, New Zealand Baptist, April 1943.

[23] F W Boreham, My pilgrimage (London: The Epworth Press, 1940), 11-12.

New Kind of Looking

New Kind of Looking Simplify!

Simplify! Become an Explorer

Become an Explorer

New Way of Looking

New Way of Looking