In our last posting we heard F W Boreham talk of the importance of children and his indebtedness to children in his preaching ministry—“The children in the congregation are my salvation.” This new excerpt is from the same sermon and he extends the themes of children and simplicity in good communication:

In our last posting we heard F W Boreham talk of the importance of children and his indebtedness to children in his preaching ministry—“The children in the congregation are my salvation.” This new excerpt is from the same sermon and he extends the themes of children and simplicity in good communication:Style of the Masters

Can anyone imagine John Wesley talking to his summer-evening crowd at Dublin about ‘nullifidian,’ or quoting German?

I will say nothing of the Galilean preacher. The common people heard Him gladly. He was so simple and therefore so sublime.

A little child, especially a little child of a distinctly restless and mischievous propensity, is really a great help to a minister, and it is a shame to deprive the good man of such assistance. It is only by such help that some of us can hope to approximate to real sublimity.

Keep Your Eyes on the Waiters

Lord Beaconsfield used to say that, in making after-dinner speeches, he kept his eye on the waiters. If they were unmoved, he knew that he was in the realms of mediocrity. But when they grew excited and waved their napkins, he knew that he was getting home.

Pick out the Stupidest

Lord Cockburn, who was for some time Lord Chief Justice of Great Britain, when asked for the secret of his extraordinary success at the bar, replied sagely, ‘When I was addressing a jury, I invariably picked out the stupidest-looking fellow of the lot, and addressed myself specially to him—for this good reason: I knew that if I convinced him I should be sure to carry all the rest!’

Speak to the Waiters

Dr. Thomas Guthrie, in addressing gatherings of ministers, used to tell this story of Lord Cockburn with immense relish, and earnestly commended its philosophy to their consideration. I was reading the other day that Dr. Boyd Carpenter, formerly Bishop of Ripon and now Canon of Westminster, on being asked if he felt nervous when preaching before Queen Victoria, replied, ‘I never address the Queen at all. I know there will be present the Queen, the Princes, the household, and the servants down to the scullery-maid, and I preach to the scullery-maid.’

Little children do not attend political dinners such as Lord Beaconsfield adorned; nor Courts of Justice such as Lord Cockburn addressed; nor Royal chapels like that in which Dr. Boyd Carpenter officiated. And, in the absence of the children, the only chance of reaching sublimity that offered itself to these unhappy orators lay in making good use of the waiter, the stupid juryman, and the scullery-maid…

Discuss Manuscripts with Your Students

Robert Louis Stevenson knew what he was doing when he discussed every sentence of Treasure Island with his schoolboy step-son before giving it its final form. It was by that wise artifice that one of the greatest stories in our language came to be written…

Expressing Love with Simplicity

We do not make love in the language of the psychologist; we make love in the language of the little child. When life approaches to sublimity, it always expresses itself with simplicity. In the depth of mortal anguish, or at the climax of human joy, we do not use a grandiloquent and incomprehensible phraseology. We talk in monosyllables. As we grow old, and draw near to the gates of the grave, we become more and more simple.

Perfect Simplicity

In his declining years, John Newton wrote, ‘When I was young I was sure of many things. There are only two things of which I am sure now; one is that I am a miserable sinner, and the other that Christ is an all-sufficient Saviour.’ What is this but the soul garbing itself in the most perfect simplicities as the only fitting raiment in which it can greet the everlasting sublimities?

Sublimity and Simplicity

‘Here are sublimity and simplicity together!’ exclaimed John Wesley on that hot July night at Dublin. ‘How can any one that would speak as the oracles of God use harder words than are to be found here? By this I advise every young preacher to form his style!’

Aspiring to be Great

‘He who aspires to be a great poet—as sublime as Milton—must first become a little child!’ declares the greatest of all littérateurs.

‘Whosoever shall humble himself as this little child, the same is greatest in the kingdom of heaven!’ says the Master Himself, taking a little child and setting him in the midst of them.

‘Pity my simplicity!’ pleads this little thing with its soft arms round my neck.

‘Give me that simplicity!’ say I.

F W Boreham, ‘Pity My Simplicity!’ Mushrooms on the Moor (London: Charles H Kelly, 1915), 153-157.

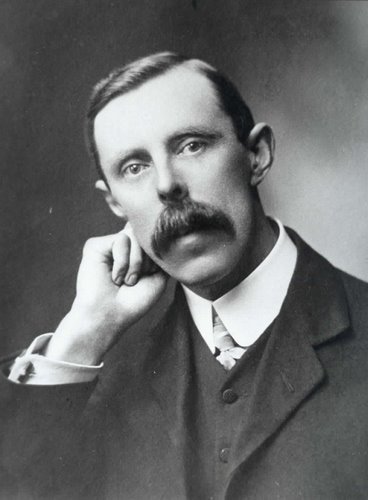

Image: “taking a little child…”