Profundity in Postage Stamps

Profundity in Postage Stamps

In December 1926, F W Boreham commenced an editorial with the question, “What can be more common-place than a postage stamp?”

[1] This was typical of the style of many Boreham editorials in which he wrote about an object or issue that was common-place and, building on the familiar, urged readers to consider something more profound. Such articles included the titles, ‘The art of holiday making’,

[2] ‘Going back to school’,

[3] ‘Harvest time’,

[4] ‘Fireside fellowship’,

[5] ‘Drinking tea’,

[6] ‘The weather’,

[7] ‘Letter writing’

[8] and ‘What’s in a name?’

[9]So Wealthy a Romance

In writing about the ordinary and the everyday, an enduring theme of F W Boreham was the notion of ‘romance’. He wrote that in everyday objects and even in the “life of the ordinary man there is a nugget of romance”.

[10] In this statement, Boreham was inferring that romance was an element that gave special value to something or someone that might otherwise have been overlooked. Continuing with this imagery, he wrote variously of “discovering so wealthy a romance in the unfolding of Spring”,

[11] the capacity of a crisis to “impart ... romance”

[12] and a writer who “went on investing reality with romance”.

[13]Pregnant but Concealed

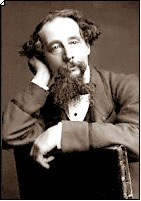

Boreham wrote that the romance of the everyday was a quality that was usually not immediately apparent. This idea was consistent with the notions in which the truth enclosed within nature’s “peels and pods”, Dickens’ “philosophy of envelopes” and Carlyle’s “concept of clothing”, provided variations on the idea of keeping the romance temporarily concealed.

[14] Boreham inferred that there was a human responsibility to mine for truths in order to procure ‘a nugget of romance’. In another editorial, Boreham alluded to brown paper and string being “pregnant with romance”,

[15] thus hinting at the way romance, while hidden within the ordinary, had a life within that was moving towards visibility.

Irresistible Fascination

Boreham believed people had an “irresistible fascination for all tales of romance”

[16] and a longing to see “fresh phases of ... romance”,

[17] yet he recognised that this sense had to be “awakened” and continually discovered.

[18] While Boreham wrote about some things in which romance was widely anticipated, as in “the romance of the throne”

[19] or the “romance of places unexplored”,

[20] he sought to cultivate a pursuit of romance in objects where it was least expected. In this regard, Boreham wrote editorials on such unlikely topics as “the romance of a recluse”,

[21] “the romance of a dictionary”

[22] and “the romance of obscurity”.

[23]Halo of Surprise

The editorials that addressed the romance of everyday things exemplified ways that Boreham encouraged a way of looking through an object. In writing about the everyday experience of work, he admitted his inability to express his vision adequately when speaking of the “indefinable atmosphere of romance”.

[24] It seemed for Boreham that the awareness of romance evoked an experience of wonder and mystery and was triggered by something that was seen. This thought arose from his frequent use of visual images in which he wrote of “an atmosphere of romance”, “a gleam of romance”

[25] or casting “a halo of romance”.

[26] Contemporary author, Annie Dillard, noted the emotional factor in such an experience when “although it comes to those who wait for it, it is always, even to the most practised and adept, a gift and a total surprise”.

[27]Illuminated by Radiance

In the foreword to one of his books, Boreham described how, walking along one day and noticing the beautiful effect of the glance of the sun on some rugged rocks, he arrived at the title of his latest book, The fiery crags. In explaining the purpose of the essays, he said, “I have simply attempted to communicate to these pages a few impressions gathered in restful moments when life’s commonplaces were illumined by the radiance that sometimes streams upon this world from worlds above”.

[28] In this revealing title and commentary that conveyed another visual image illustrating romance in the everyday, Boreham alluded to further significant convictions.

While it has been noted that the discovery of romance must be worked at like a miner or pursued intentionally like an explorer, Boreham’s experience of momentarily seeing the fiery crags highlighted the elusive nature of romance which cannot be manufactured but may flash in the eyes of those with the patience to see. His mood for welcoming such an elusive experience was reflective rather than rational, contemplative more than cerebral. In this foreword to his book of religious essays, Boreham hinted at the spirituality of the experience and its divine source.

Geoff Pound

Image: Parable of the Postage Stamp

[1] F W Boreham,

Mercury, 11 December 1926.

[2] Boreham,

Mercury, 9 January 1915.

[3] Boreham,

Mercury, 15 January 1916.

[4] Boreham,

Mercury, 18 December 1928.

[5] Boreham,

Mercury, 22 June 1957.

[6] Boreham,

Mercury, 6 December 1930.

[7] Boreham,

Mercury, 6 March 1926.

[8] Boreham,

Mercury, 24 September 1927.

[9] Boreham,

Mercury, 1 September 1917.

[10] Boreham,

Mercury, 9 December 1933.

[11] Boreham,

Mercury, 29 December 1945.

[12] Boreham,

Age, 26 February 1949.

[13] Boreham,

Mercury, 20 August 1927.

[14] Boreham,

Age, 4 September 1954.

[15] Boreham,

Mercury, 22 December 1956.

[16] Boreham,

Mercury, 29 December 1945.

[17] Boreham,

Mercury, 4 March 1944.

[18] Boreham,

Mercury, 26 May 1956.

[19] Boreham,

Mercury, 18 April 1925.

[20] Boreham,

Mercury, 4 February 1939.

[21] Boreham,

Mercury, 12 July 1952.

[22] Boreham,

Mercury, 15 May 1932.

[23] Boreham,

Mercury, 9 December 1933.

[24] Boreham,

Age, 26 February 1949.

[25] Boreham,

Age, 29 March 1941.

[26] Boreham, Age, 3 January 1953.

[27] Annie Dillard,

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (New York: Perennial Classics, 1985), 35.

[28] F W Boreham,

The fiery crags, 7-8.

Hidden Treasure

Hidden Treasure

Romance of Monotony

Romance of Monotony

New Kind of Looking

New Kind of Looking Simplify!

Simplify! Become an Explorer

Become an Explorer

New Way of Looking

New Way of Looking

Vision for the Ordinary

Vision for the Ordinary Boreham and Dickens

Boreham and Dickens Secret to His Success

Secret to His Success