Boreham and Dickens

Boreham and DickensIn an earlier posting we have discussed the similarities between Charles Dickens and F W Boreham—those things which may have urged Boreham to lean on Dickens for inspiration. To recapitulate, they were both reporters, they both learned shorthand to help their journalistic writings, they both had stints at editing newspapers, their popularity grew through their stories that were first printed in newspapers and later were compiled into many books, they both liked to visit the scenes they were describing and they had retentive (photographic?) memories.

There is one other significant area for comparison and this focuses on the theme of this series of postings—their vision for ordinary people and things and their ability to capture the colour and the detail of everyday life in words and pictures. This is one of the big secrets behind their popularity and success as communicators in their age.

Artist in Real Life

We have already seen how the English novelist Charles Dickens shaped Boreham’s literary style but let us focus specifically now on how Boreham understood Dickens’ views and descriptions of the ordinary. The reason why Boreham praised Dickens as “an artist in real life” was because of the novelist’s commitment to study and know ordinary life. In Boreham’s words, “he saw humanity in every garb and from every conceivable angle. The panorama fascinated his hungry mind”.[2] Characteristic of the Dickensian style was the telling of stories about common things and common people. Quoting Compton-Rickett’s tribute to Dickens, Boreham wrote, “He is great because, though dealing continually with little worries, little hardships, and little pleasures, he made the dullest of lives in the drabbest of streets as enchanting as a fairy tale”.[3]

Love is Notoriously Blind

A compelling stylistic feature for Boreham was Dickens’ “unswerving fidelity to truth” yet, through “the melting pot of his vigorous mentality”, Boreham recognised that Dickens expressed his own rendition rather than presenting an accurate reflection of what he saw. However, in Boreham’s reckoning, these two features could coexist without contradiction, for when noting Chaucer’s transparent honesty, yet conceding validity in the public criticism of Chaucer’s depiction of an idealised England, he said: “Love is notoriously blind. When a lover describes his lady, everybody knows that, though he may be the soul of veracity, he is not telling the whole truth. He has no eyes for the faults and foibles that seem so conspicuous in the sight of others. So was it with Chaucer, and, on the whole, we like him all the better for it”.[4]

Ringing with Reality

Despite questions as to Dickens' faithfulness in articulating his vision, it was his descriptions of ordinary people, everyday moods, typical scenes in recognisable places such as the kitchen, the club or the street that delighted his readers. Writing about everyday human experience led Boreham to say of Dickens that “his pages carry conviction; they ring with reality”.[5] The familiarity of his creations produced an affinity rather than contempt.

In contrast to Shakespeare and Milton, whose devotees took time to appreciate their worth, Boreham said that Dickens experienced an immediate response of appreciation that vindicated his passion for writing about the commonplace. Boreham explained Dickens’ secret as “life answers to life, as, in another connotation, love answers to love”.[6]

Geoff Pound

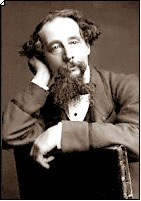

Image: Charles Dickens

[2] F W Boreham, Mercury, 9 June 1951.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 12 June 1920.

[4] Boreham, Mercury, 2 September 1933.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 12 June 1920.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 9 June 1951.