If you have read several of the books by F W Boreham you will not be the first person to have asked the question, “Who was John Broadbanks?” Helen, a frequent reader of this web log, has recently asked the question and specifically enquired as to whether I had asked the question of Dr Boreham’s son, Frank Boreham Jnr. Here is my response.

If you have read several of the books by F W Boreham you will not be the first person to have asked the question, “Who was John Broadbanks?” Helen, a frequent reader of this web log, has recently asked the question and specifically enquired as to whether I had asked the question of Dr Boreham’s son, Frank Boreham Jnr. Here is my response.From his books these are some of the details we can glean. The Rev John Broadbanks was a neighboring minister at Silverstream when Boreham was pastor at Mosgiel,New Zealand. Both of small towns are real places (there is a photo of Silverstream in Boreham’s booklet, ‘The Empty Pitchers’) and are about 10 kilometers apart, from memory). Boreham doesn’t say but it would seem Broadbanks was a Presbyterian minister.

Boreham and Broadbanks were close friends and on their day off (Monday) they alternated their weekly meetings at each other’s manse. They went on shooting expeditions, holidayed together, visited churches in outlying areas, swapped sermon ideas and shared the deep things on their hearts.

Broadbanks appears to have been older than Boreham. He was married to Lilian and their daughter, nicknamed Goldilocks, is mentioned in one of Boreham’s essays. Boreham once wrote: “The best debater that I ever knew was John Broadbanks.” In another essay he wrote that John Broadbanks had “a superb gift of mimicry and was a fine actor.”

John Broadbanks suffered a breakdown in health (so did FWB) and came to the resolution that he would be faithful to the basics of ministry and not take on every invitation (again, Boreham’s personal resolve).

John’s death had a profound effect on Boreham, leading him to write, “With the passing of John Broadbanks I myself must pass.” This book, ‘The Passing of John Broadbanks’ was published at the time of Boreham’s retirement in 1928 and was to be his last book. A couple of years later a new book appeared (he suffered from an ‘incontinent pen’) and he went on to write another twenty books!

F W Boreham used the profits from his books and preaching to establish and fund the ‘John Broadbanks Dispensary’, in Birisiri, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Calling it by this name was a way of diverting attention away from himself.

What did F W Boreham say about John Broadbanks? T Howard Crago, his biographer, asked him this question and his answer was quite unclear!

When I quizzed Dr Boreham’s son, this is what Frank Boreham Jnr. said:

“I have given a lot of thought to the person of John Broadbanks and I talked to Howard Crago about it. There is a general consensus that when my father wanted to introduce a character e.g. his wife and did not want to refer to my mother she would be John Broadbanks. Sometimes he would be John Broadbanks. He talked about it. My father refers to Silverstream, the place where John Broadbanks lived, because when you go there the manse is right on Silverstream. So when he wanted to talk about himself he talked about John Broadbanks.”

I agree with this conclusion and find some support for this literary technique among some of Boreham’s literary models. Here is what I wrote a few years ago on this subject:

One of Boreham’s famous fictional characters was the enigmatic, John Broadbanks,[1] In Boreham’s development of John Broadbanks it is possible to see traces of the Dickensian “tendency toward multiple projection”[2] and the way Dickens developed “sides of himself in all the major figures in his moral and social spectrum, male and female, young and old.[3]

Boreham concealed his thinking behind the guise of ‘John Broadbanks’ and particularly in his editorials he displayed a [Mark] Rutherford-like restraint in refraining from references to himself. A [rare] example of authorial disclosure is found in an editorial about Catherine Booth which Boreham implies that he had attended her funeral.[4]

It may have been Boreham’s immersion in the Scottish province of Otago that led to his acquaintance with a variety of Scottish writers who left their mark on his writing style. Among these was James Matthew Barrie whom Boreham described, with his characteristic use of superlatives, as “the most distinctive, most outstanding and most lovable figure of his time”.[5] Perhaps it was Barrie’s popularity in immortalising obscure Kirriemuir and projecting himself in the “impish McConnachie” that led Boreham to write his essays about country town Mosgiel and project another side of his personality into the character of John Broadbanks.[6]

Like Boreham, temperamentally “shy and sensitive”, Barrie’s great gift was “the ability to invent and tell a good story”.[7] Boreham alluded to the virtues of restraint and anonymity which were most evident in his editorials when he said of Barrie, “There is a sense in which he never speaks of himself: there is a sense in which he puts himself into every word that he utters. Therein lies his charm”.[8]

For literary license and Boreham's personality makeup it would seem that John Broadbanks was a fictional character who is made to take on different personalities at different times, be a spokesperson for wisdom and an exemplar of good living. Still, John Broadbanks remains a mystery.

While the identity of John Broadbanks is enigmatic this should not prevent us from benefiting from his contribution. Jeff Cranston expressed it well in a recent posting on this site:

“There is much wisdom and insight to be gained for every minister as the reader meets Pastor John Broadbanks of Silverstream, surely one of the choicest ministers who ever lived. He and Boreham were inseparably linked in life; you will delight in learning about John. His knowledge, expertise, and sagacity will be a boon for every minister struggling with the daily challenges presented by both the ministry and people.”

Geoff Pound

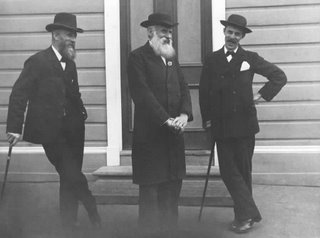

Image: Boreham is on the right but is John Broadbanks one of the other two?

[1] For examples of the way Boreham developed the Broadbanks figure see Boreham, Ships of pearl, 163, 223. An analysis of the Broadbanks phenomenon is found in Crago, The story of F W Boreham, 98, 74, 225.

[2] A Welsh, From copyright to Copperfield: The identity of Dickens (Cambridge; Harvard University Press, 1987), 28, 45.

[3] M Golden, Dickens imagining himself: Six novel encounters with a changing world (Lanham: University Press of America, 1992), 4.

[4] Boreham, Mercury, 4 October 1947.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 9 May 1942.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 9 May 1942.

[7] James A Roy, James Matthew Barrie: An appreciation (London: Jarrolds Publishers, 1937), 48.

[8] Boreham, Mercury, 9 May 1942.