I am Debtor

I am DebtorOver the last 15 postings we have examined the novelists and historians who shaped the writing of F W Boreham. To all these people and others Boreham was indebted.

Editorials in Scrapbooks

F W Boreham’s 3,000 editorials were printed in the Otago Daily Times, the Hobart Mercury, the Melbourne Age and there were a few in The Argus. Thankfully he or a relative cut these out and pasted them into large scrapbooks which are kept at the F W Boreham Collection at Whitley College in Melbourne. From his scribblings in the margin and blue crayon (signifying that he used that editorial in the Age) one gets to see how Boreham recycled his articles.

Detective Work

Unfortunately the scrapbooks do not contain Boreham’s editorials from the Otago Daily Times and there is a scrapbook missing from 1914-1917 (from memory). When I read Boreham’s editorials in old copies of the Otago Daily Times and the Mercury on microfiche at the Victorian State Library over these periods I had to guess which of the unattributed editorials each day belonged to Boreham. Fortunately by that time I had read hundreds of his editorials and had become proficient at detecting his work. This posting seeks to identify his style and describe Boreham’s literary signature?

Literary Style Arises out of the Person

In writing about literary style, Boreham drew attention to the diverse approaches of some of his models: “You can’t understand their styles unless you understand them. For their styles are simply themselves .… If you were to put a sentence of Carlyle into Gibbon or Macaulay ... each of these sentences would seem as much out of place as a cuckoo in a robin’s nest. Their style is peculiarly and exclusively their own.[1]

Who was the literary Boreham and how did his personality find expression in his unique writing style? In what ways did his writing bear the marks of those he selected as ‘worthy models’ of the literary art?

Lover of Words

Boreham was a lover of words who possessed a passion to write. His reserved temperament and shyness with people, which he shared with many of his role models, may have found compensation in his extroverted pen. He would have agreed with the current editor of the Age, Michael Gawenda, who wrote, “There is a magic about printed words on paper that cannot be replicated by any other form of communication. There is something about printed words on paper that goes to the heart of what defines us as human beings, that speaks to our deepest needs”.[2]

Those whom Boreham anointed as his models were wordsmiths who approached their craft with reverence. The training in shorthand and journalism that he shared with many of his mentors made Boreham attentive to tone, to the sound of words and how they would be received by his readers. With Walter Landor, he wondered at the intrinsic beauty of words and believed that the artistic selection of words was “what melody is to the composer, what colour is to the painter”.[3]

Lover of Stories

Moreover, Boreham was a lover of stories who adopted storytelling as his major literary form. While Charles Dickens introduced him to the enchantment and entertainment of stories, Gibbon, Macaulay and Scott extended his appreciation of the use of a narrative style for presenting personalities, motives and movement. Boreham’s writing possessed a predictable structure but it relied heavily for its colour and appeal on dramatic movement, concrete images, eye-catching detail and a preoccupation with people—particularly little, unassuming people. A revealing gift that Boreham shared with Dickens, Gibbon and Macaulay was an unusually retentive and imaginative memory that aided the study of a scene and the ability to portray it in words with artistic flair.

Lover of History

Further, Boreham’s love of history was meteoric yet enduring. He liked to set the present situation within an historical context, to encourage a respect for the past and to draw lessons from the past for future living. His reading of the story of England instilled within him a pride in the nation’s achievements and heightened his sense of optimism and progress about the British Empire. From Macaulay, Gibbon and Scott he learned to write history in a narrative style, enshrining principles within his many biographical editorials. His person-centred view of history was sanctioned by Thomas Carlyle who championed the importance of recalling great heroes. Boreham’s belief that history needed to be told in an interesting and graphic fashion often led to a lack of analytical depth and a “dangerous simplicity”.[4] Being attentive to how his readers were enjoying his work, Boreham’s propensity to daydream enabled him to climb into characters and explore contexts but, as with Gibbon and Macaulay, his self-projection led to a loss of historical objectivity.

Lover of Style

In addition, Boreham’s writing displayed a love of style. While attentive to the diverse approach of different authors, he was adamant that writers must find their unique style. Boreham was also conscious of the need for a speaker or writer to change with the times when he wrote in 1916, “The pompous phrase, the superb figure, the classical quotation and the irridescent glow of the elaborate peroration are among the things that have had their day and ceased to be”.[5] He recognised style as a “reduction of one’s personality to paper” and an expression of one’s God-given creativity which may be developed through study and practice.[6] He admired the forthrightness of Macaulay and Carlyle and derived from them a confidence. However, Boreham’s written expression was a reserved, dignified style that he described as portrayal in “pastel shades” rather than black and white.[7] This was his customary style by personality and conviction. While Boreham’s early literary efforts appeared wordy and cumbersome, from Gibbon he came to value clarity. Boreham’s commitment to authorial restraint contributed to the “crystalline” style.[8] From models such as John Bunyan and Mark Rutherford, Boreham prized the qualities of simplicity and a naturalness of expression. Boreham revelled in the energy that pervaded the writings of Robert Louis Stevenson and he, in turn, strove to achieve a style where aptly chosen words might throb, exude joy, elicit insight and transport readers on a journey of discovery.

Geoff Pound

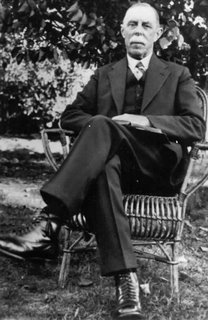

Image: F W Boreham seated in his cane chair at Fellows Street in Kew, Melbourne. Circa, 1956-59.

[1] Boreham, When the swans fly high, 130-131.

[2] Michael Gawenda, Age, 1 November 1999.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 20 October 1934.

[4] Porter, Edward Gibbon: Making history, 7.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 24 June 1916.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 12 March 1938.

[7] Boreham, Age, 27 April 1946.

[8] Boreham, Mercury, 16 March 1957.