Developing a Consciousness of History

Developing a Consciousness of HistoryWhile F W Boreham challenged historians to write in a more appealing manner, he also addressed the reluctance of readers to develop a historical consciousness. Since 1888 when Henry Lawson complained about the abysmal historical knowledge of children and the failure of the education system, Australian patriots and historians have regularly deplored the neglect of the nation’s history.[1]

Addressing this neglect sometimes meant for Boreham dispelling the common notion “to let bygones be bygones”,[2] but what disturbed him most was Edward Gibbon’s indictment of the Athenians whose decline was apparent in their “indifference to antiquity”.[3] Boreham judged that “to such a depth of degradation Australians have not fallen”;[4] however, the disinterest of most Australians towards history puzzled Boreham in respect of both the Australian personality and the quality of the Australian heritage. With characteristic tact, Boreham explained, “Among the virtues generally attributed to the typical Australian, modesty does not always find a conspicuous place”.[5] Why was it that Australians were, therefore, bashful or diffident about their past? He continued, “For some reason or other, the Australian is singularly reluctant to emphasize and commemorate the magnificent exploits which adorn his history”.

Boreham was not a lone voice on this theme. After their marathon trek across Australia, Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen expressed in 1912 their disgust over the lack of recognition for the early explorers, saying, “Australia cannot be congratulated in the way in which she has treated their memory”.[6] Historian Geoffrey Serle offered an insight into Australian attitudes towards heroes when saying, “No outstanding twentieth-century Australian leader … has retained full acknowledgement as a great man. Australians are not given to praising famous men or making legendary heroes of many, other than bushrangers and sportsmen”.[7]

Give Them The Facts

In another editorial on the same theme Boreham concluded that Australians “are guilty of want of thought rather than want of heart” and in order to escape this judgment “they will have to pay a little more attention to, and take a little more pride in, those glowing records that illumine the initial pages of Australian history”.[8] In an article commemorating the centenary of the exploits of Hamilton Hume, Boreham reiterated his view that the problem lay in a lack of information. He said, “Australians may have their faults; but if they are placed in possession of the facts, they never fail in appreciation of the splendid intrepidity and dauntlessness of those brave men who blazed the first trails across the continent”.[9]

Tide Turning

In the last two decades of the twentieth century commentators have observed the growing appreciation of history and the increasing role of historians in Australian public life.[10] Bruce Wilson offered examples to illustrate how this shift in attitude has been taking shape:

"The past two decades have seen an unprecedented interested in our national history …. Books on every conceivable aspect of Australian life, culture and the natural environment have poured from the presses. The Australian film industry has resurrected our past as well as itself. Nostalgia has recreated ‘living history’ at old Sydney Town, Sovereign Hill, Timbertown and elsewhere …. Women have begun to stake their claim to a place in the new national myth, rediscovering legendary figures like Caroline Chisholm and Miles Franklin."[11]

National History Needed

Boreham would have been heartened to see a new era of national myth-making emerge but Wilson’s comments suggest that the early Australian reluctance towards history that Boreham identified may not only be attributed to a lack of information but also to a lack of information about Australian history. Boreham was realistic about the task of awakening Australians to their past but his knowledge of history encouraged him—particularly the example of Sir Walter Scott who, when faced with the Scottish national spirit needing to be revived, “convinced himself that the torpid and lethargic Present needed to be brought in contact with a splendid and stately Past”.[12]

Reminding People of their Past

Boreham viewed his editorial responsibility as reminding Australians of their past and thus increasing their pride about their national heritage. His recognition that this task had importance for the future was revealed in his frequent reference to Macaulay’s axiom that “a people who takes no pride in the noble achievements of its ancestors will never achieve anything worthy to be remembered by its remote descendants”.[13] He elaborated on this thought when, in an editorial marking the achievements of the South Australian explorer John Billiatt[14] he asserted, “The more people know of the struggles and conquests of the past the more will they be willing to sacrifice and suffer in order that their spacious land may enjoy a destiny worthy of her monumental traditions”.[15]

Remembering our Debts

Boreham regularly addressed this theme in editorials commemorating those who had died in war and in writing of “the incalculable debt” that the living owed to its ancestors.[16] He said that “our solemn obligation to remember” is incumbent upon readers because “in the memory of survivors the dead live on”.[17] Enlarging on this thought, he said that by being remembered, such people, “fulfil their destiny” or “complete their life work”, an idea he attributed to Paul of Tarsus who “averred that his life work consisted in ‘filling up that which is lacking in the sufferings of Christ’”.[18]

Freedom From Apron Strings

While keen to extol the value of acquiring a knowledge of history, Boreham did concede some negative aspects. On Australia Day in 1951, he said that Australia’s challenge in creating a distinctly indigenous literature was “not because of aesthetic deficiency or intellectual poverty, but because of the extreme difficulty of shaking herself free of the monumental traditions that she had inherited”.[19] This observation, however, did not prevent Boreham from stating in the same article that Australia should recall at every opportunity that “the best life of the younger nations—America and Australia—is rooted in the spiritual pulsation that swept the Motherland”. In another article on developing a unique Australian style of music, Boreham alluded to the same limitation but said that Australia, compared with other countries, “is less hampered and trammelled by antique traditions”.[20]

Geoff Pound

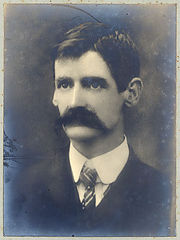

Image: Henry Lawson

[1] Henry Lawson, ‘A neglected history’, Henry Lawson: Collected verse, ed. Colin Roderick, vol. 2, Autobiographical and other writings 1887-1922 (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1972), 6-8.

[2] Boreham, Mercury, 22 June 1946.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 14 June 1919.

[4] Boreham, Mercury, 10 October 1925.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 13 June 1936.

[6] B Spencer and F J Gillen, Across Australia vol. 1 (London: MacMillan & Co., 1912), 29-30.

[7] Geoffrey Serle, John Monash: A biography (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1982), 529. In writing about Simpson and his donkey in the Anzac legend, Les Carlyon adds a further insight to this theme when he said, “Australia likes quirky heroes”. Les Carlyon, Gallipoli (Sydney: Macmillan, 2001), 267.

[8] Boreham, Mercury, 10 October 1925.

[9] Boreham, Mercury, 13 January 1923.

[10] Graeme Davison writes, “History is often in the headlines. Never before, perhaps, have historians occupied as prominent a place in Australian public life”. Davison, The use and misuse of Australian history, 1.

[11] Bruce Wilson, Can God survive in Australia? (Sutherland: Albatross, 1983), 108.

[12] Boreham, Mercury, 9 February 1946; Age, 16 December 1950.

[13] Boreham, Mercury, 11 October 1924.

[14] John W Billiatt was one of ten men led by the famous explorer, John McDouall Stuart, who were part of the team that successfully completed the ‘South Australian Great North Exploring Expedition’. The team left Adelaide during October 1861, and, crossing the entire continent, reached the Indian Ocean on 21 January 1862. Details of Billiatt’s life including his birth date are scanty; however, he was the last surviving member of Stuart’s successful party and he died in England in 1919. More information can be found at www.northernexposure.com.au/stuart.html

[15] Boreham, Mercury, 16 August 1919.

[16] Boreham, Mercury, 27 January 1951.

[17] Boreham, Mercury, 6 November 1948.

[18] Col. 1:24.

[19] Boreham, Mercury, 27 January 1951.

[20] Boreham, Mercury, 6 July 1935.