No More Sterile Histories

No More Sterile HistoriesMany of Boreham’s editorials reflected the Romantic historians’ commitment to literary technique. Like Macaulay, Boreham condemned the sterile work of the philosophical historians.[1] He often said that the paucity of good historical writing was because so many writers were “at their wits end for a subject [and were] driven to history because history is ready made”.[2]

Furthermore, he reckoned that the character of the historian’s task had been underrated and reduced to the mere recital of events.[3] “History,” he continued, “for the most part is wooden, stilted, lifeless, unconvincing. It is dignified but dull”. He launched his criticisms upon historians who wrote too abstractly and failed to pitch their ideas towards the average reader. In so doing, he noted: “The average historian takes us too seriously. He proceeds on the somewhat embarrassing assumption that we are all very learned, very erudite, very scholarly. He adopts the classical accents of the academy and the forum. He talks ponderously and philosophically. He misunderstands us. In reality, we are mere children”. [4]

Reflection of Real Life

Boreham’s criticism of most historians and his demanding standards arose from his conviction of the importance of the historian’s task. He believed that “history is the reflection of real life, and we have a right to demand that it shall be lifelike”.[5] Again, adopting the reflective imagery, Boreham said, “Life, whether past or present, is a most intriguing affair, and all that we ask is that the historian shall enable us to see it clearly in the crystal mirror of his story”.[6]

Colorful and Picturesque

Boreham’s many references to his editorial writing as a ‘sketch’, ‘portrait’ or an ‘idyll’ were more than metaphorical. According to Levin, “the romantic historian considered himself a painter” and Boreham saw himself in this tradition.[7] Always attentive to the impact of writing on its readership, Boreham added, “Nothing appeals to men like the pictureque. We are inveterate sightseers. We love to see things .… Did they wear red breeches or grey?”[8] In writing about pleasing historical style Boreham indulged his fondness for the attention-grabbing power of stories, colourful imagery that enabled readers to see the history and the ‘passion for trifles’, agreeing with the literary historian, Arthur Compton-Rickett, that “no detail is unworthy of mention”.[9] In the tradition of the romantic historian, Boreham “compared history to drama almost as often as [he] compared it to painting”.[10]

Vivid and Accurate

Boreham was aware that the historian must not yield to the temptation to “make his pages a wearisome recital of uninteresting and unimportant events” nor to the opposite temptation “to make his chronicle readable by spicing it up”. In order to achieve historical writing that is truthful yet interesting, Boreham outlined the following essential gifts: “The historian needs the vivid imagination of the novelist; he needs the mathematical accuracy of the scientist; he needs the penetrating insight of the philosopher; and he needs the musical temper and graceful diction of the poet. He needs all these in combination, and he needs them all at every turn”.[11]

Skipping Over the Dry and Dusty?

One wonders how often facts were ignored to enhance the drama of the story and how many historical themes Boreham shelved, like William Prescott (another person switched on to writing history by reading Gibbon) who only chose subjects that could be made “novel, elegant, useful and very entertaining”[12] and George Bancroft who “combined all the elements necessary in his History to make it the most popular literary and scholarly embodiment of the optimistic, democratic faith of nineteenth century America”.[13]

History Forging Connections

Boreham showed little evidence of a critical approach to history which “interrogates and condemns” the past or studies the past to evaluate the significant aspects of the lives of people who lived in a former age.[14] He understood history’s primary use in the way it connects peoples with forgotten ages and inspires them with their spirit.

Geoff Pound

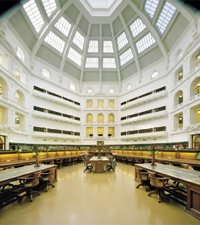

Image: Victorian State Library in Melbourne, where F W Boreham read and researched many of his historical essays.

[1]Thomas Macaulay, The works of Lord Macaulay ed. Lady Macaulay, vol. 5 (London: Longmans, Green & Co, 1866), 152-56.

[2] Boreham, Mercury, 20 November 1920.

[3] Boreham, Mercury, 26 February 1938; Age, 4 January 1947; Age, 1 October 1949.

[4] Boreham, Mercury, 20 November 1920.

[5] Boreham, Mercury, 1 October 1949.

[6] Boreham, Mercury, 26 February 1938.

[7] Levin, History as romantic art: Bancroft, Motley, and Parkman, 12.

[8] Boreham, Mercury, 20 November 1920.

[9] Boreham, Mercury, 26 February 1938. Arthur Compton-Rickett (1869-1937) is best remembered for his History of English literature from earliest times to 1916 (London: Nelson, 1964) and Lost chords: Some emotions without morals (London: A D Innes & Co., 1895).

[10] Levin, History as romantic art: Bancroft, Motley, and Parkman, 19.

[11] Boreham, Age, 4 January 1947.

[12] William H Prescott, Notebooks IV, Prescott Papers (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society), 80-81.

[13] David B van Tassel, ‘George Bancroft 1800-1891’, in Encyclopedia of American biography 2nd ed., eds. John A Garraty and Jerome L Sternstein, vol. 1 (New York: HarperCollinsPublishers, 1996), 59.

[14] Graeme Davison, The use and misuse of Australian history (St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2000), 14.